The government and the banks continue the war of words about lack of lending. In the meantime what do you do?

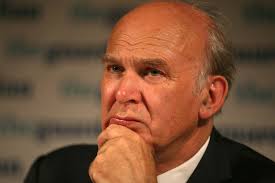

The secretary of state for business, Vince Cable,

has repeatedly expressed the coalition’s concerns about the failure of

the banking system to lend to business. Lawrence Tomlinson, the millionaire government adviser who is the ‘entrepreneur in residence’ at the Department of Business,

repeatedly accuses banks of failing to lend, often using colorful

language to do so. He has compiled a dossier of complaints from

businesses cataloguing instances of refusals to lend and in some instances the charging of “astronomical” fees.

Vince Cable has asked for a number of complaints involving the state backed lender RBS to be considered under its recently announced independent review of banking practices.

At

the same time the Bank of England says that lending to small businesses

rose by £238 million between May and June – the biggest monthly rise

since data was first recorded in 2011.

However

the government and the banks chose to slug it out in the war of words

the simple truth is that all banks have tightened their purse strings

since the banking crisis. There are a number of ways that individual

businesses may be affected by this. It is difficult to obtain recourse

where a bank simply refuses to entertain an application for funding. However I have seen an increasing number of instances where banks have refused to lend where there is already some form of obligation to lend.

The

most typical scenario, although not the only one by any means, is where

a bank has agreed to lend to a business for a particular purpose and

advances part of the amount required whilst promising that if certain

criteria are met the necessary further funds will be forthcoming. The

business proceeds with its project in good faith incurring a liability to the bank for the funds advanced. When the further funds are required the

bank refuses to advance them and the project fails leaving the business

with nothing other than a liability to the bank rather than successful

completion of the anticipated project.

At

one level this could be a verbal understanding reached with the

business’s bank manager that may be referred to only briefly in e-mails

but is not ultimately reflected in the bank’s formal documentation. A

more formal example is property development funding where the bank has

lent funds for property acquisition and also agrees to provide development funding. Contracts,

usually on the bank’s standard forms, are in place. A change in bank

policy often means that the bank suddenly looks for any excuse to get

out of its commitment to advance development funding. In these circumstances it is not unusual for the bank to allege breach of some financial covenant in the lending agreement.

It

is a fact of business life that parties to business transactions may

behave badly. A bank can avoid promises to lend if the contract between

it and the borrower allows it to do so. Any business that has been

affected in this way has to examine exactly

what the legal obligations of the bank are. This can depend on

construing not only the bank’s standard documentation but also

communications passing between the bank and the borrower and the full

history of the banking relationship.

If the business owner has given a personal guarantee then his or her personal assets are potentially on the line as well.

Once

the full picture is ascertained in this way the position of the parties

may not be as it appears from a first reading of the bank’s

documentation

and the bank may not be able simply to avoid liability for its failure

to lend. The bank may also be unable to claim on any security, such as a

personal guarantee, that it may have taken at the outset.

Recourse

against banks in these situations is never guaranteed but it does pay

to look beyond the standard form documentation before deciding on the

legalities of any given situation.

www.patrickselley.com